Performing Arts Forum

23.-27. July, 2018

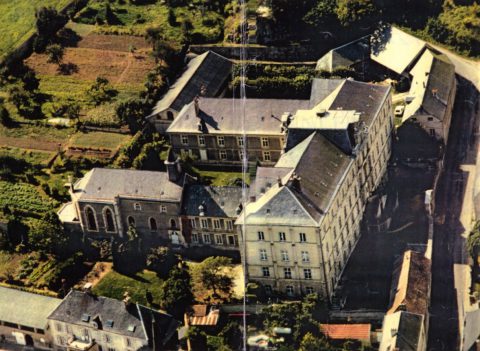

(St.Érme, FR)

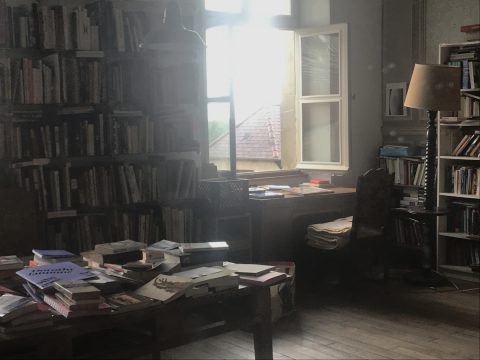

PAF is a place for the professionals and not-yet-professionals in the field of performing arts, visual art, music, film, literature, new media, theory and cultural production, who seek to research and determine their own working conditions. It has no staff and is partly, on the level of its daily functioning, self-organised.

We visited PAF together with Caique, Norbert and Sheena in summer 2018 and spoke with various people about this place, their work and their affective involvement with it, starting with Stéphanie who has been supporting PAF’s organisational and administrative structure for several years.

Stéphanie is one of the very few permanent presences taking care of PAF with regard to tasks that need regular attention.

Jean Félix is also one of the very few permanent inhabitants. Although PAF does not have any staff, he is taking care of PAF’s physical building.

https://vimeo.com/378415689

Norbert, who introduced us to PAF and its inhabitants, is one of 50 shareholders, co-owning the building.

Translated transcript of this interview:

What kind of place is the PAF to you?

Good question. PAF is a place that is changing. That’s one thing. But it’s also a place I can always return to. At least I believe that I can be there in both a self-determined way and in contact with others. Currently, it has also become a place of responsibility for me and I ask myself how I can support the place.

When I first came here, it was a bit of an accident. Friends went to this Spring Meeting— I would need to find out what year that was—so I came to PAF for the first time, and it was at first a place of overload. It took me quite a while to get out of my room. But then it became a place of intense stimulation, especially at the intellectual level. That was my incentive to come back again and again and to see: something is happening here. And then it quickly became a place with which I can identify in a certain way. I think it’s a home that doesn’t have the cosiness of a home. A place, where I must constantly question myself in terms of how I do things, how I interact with others, but [it’s a place], where others also give space to me to come back again and again or to reinvent myself. Yes, that’s what the place is to me.

You are one of the shareholders. What moved you to become one?

It was in the summer three years ago. I was smoking a cigarette outside with Daniela and she was the first one to tell me about it and I was like: “What?” Twenty thousand Euros is a lot of money for me, which I didn’t have at the time. Then they said, “You can pay in instalments; that would be totally cool” and then I thought about it and we talked about whether it was a good investment or not. It’s not a good investment because we’ll never be able to get more than 20,000 out of here, that’s what we’ve contractually agreed. But Daniela convinced me when I said to her, “Don’t you think it’s risky? Who knows what happens to PAF if suddenly nobody comes around anymore,” and she replied, “Oh, nonsense, on the contrary, the tendency towards people being nomadic is increasing and they will always need a place of refuge.” I thought that was a very good argument.

For me, the project itself first consists in collectivising property in a different way than, for example, having an apartment in a cooperative housing project, where there is a clear definition of: “This is my apartment—this is yours.” I’m interested to see if something really crazy can be created together. For example, to secure a monastery in the long run for many people who don’t have any money, so that they have a place where they can work luxuriously and seriously. And to participate in such a gesture was very attractive to me. To show that it is possible after all, that you don’t have to work hard all your life to buy something that you then somehow make available for a good cause, but that we can already actively create a small utopia together, one could say.

And the other aspect is PAF concrete. So when I say PAF concrete, I mean the real estate.

The real estate belongs to us (shareholders), but we can’t determine what happens there because it is rented by PAF, the association in which you now also are a member. This means that all (association members) can have a say in what happens in the property. PAF (the association) rents the real estate from us (the shareholders) and pays what is necessary to cover the energy costs and similar things. By becoming owners, we are no more involved in the PAF project than others who come here. But at the same time, I have a feeling as if I have tied myself to PAF with this investment. There is a shareholders’ meeting at the end of each year.

It’s a lot of work but many of the themes are interesting and are addressed in relation to the building. Thus, they no longer remain abstract, such as the question of property or how to create common property. What is solidarity, what is fluidity of property etc.? It concerns many things that I suffer from in everyday life. At the time, I still lived in Frankfurt and it’s hard to survive there at all. It partly leads to loneliness and partly to a strong fear of the future, in the long run but also in the medium term. I’ve never had a job where I had a regular income, so the question often was, How do I pay my rent now? Paradoxically, the investment now rather means that there is a phantasmagoric place where I can be even if I know that I can’t be here for more than 30 days until I must start paying rent—and sometimes even more than I paid in Frankfurt. It means that I couldn’t afford to be here permanently. But still there is this dream-like place that belongs to many, with a concrete form of solidarity, which actually isn’t one. It’s not like within a family. It doesn’t have the warmth of a family, but it does convey a form of security.

How do you make decisions?

The main idea is to discuss things, formulate arguments and try to convince others. There are certain decision-making panels, I think, but I’m not sure what the current state of affairs is. But I know that we’ve talked a lot about anonymity being important. Especially when it comes to deciding for or against someone new. It might not be productive—or at least I didn’t think it was productive—for example when one person has a problem with another person and then everyone presses to convince them or something. But like I said, I’m not sure what the current state is.

We have one vote per person. People who cannot attend can be represented by another person. We make sure that as many people as possible are represented, so we actively approach the people we know will not attend. I think there is also a president and an accountant or treasurer. There are a few functions preparing these meetings. It partly overlaps with PAF. Representatives of PAF also come to report on the year. There are representatives of the building who say, “This was done in a renovation, this is about to be done, this needs to be done.” We then have regular discussions about the prices that PAF pays to us shareholders for the use of the building. These prices also influence the overnight fee and the general concern is to lower this overnight fee. So, we consider whether the price level is really appropriate. All 50 shareholders are equal or have equal voting rights.

What is the role of PAF?

PAF is basically the entire operation of the building. What does that mean? Everything that makes life here: welcoming people who want to work here, organising events like the Spring Meeting or Winter Meeting, Summer Meeting, evaluating whether new formats like these can come into being. Whether they are about the…

PAF is also a mailing list, so PAF is a living organ. Or a being. The question is: what kind of information is sent into the world as PAF? It’s about the external presentation of PAF, one could say. And about welcoming people here, the whole administration. PAF takes care of all the rooms, that there are bed sheets, that shopping is done, so the life in the building is organized by PAF.

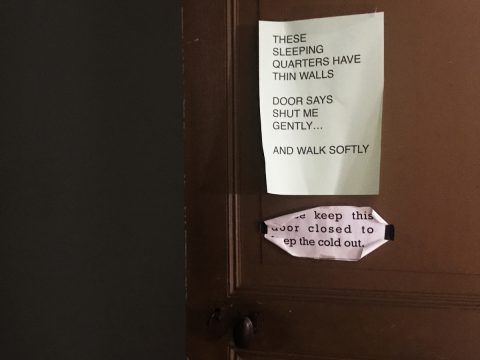

There is also a lot of work that has to be done on top of concrete work like, “Something is broken, it needs to be replaced”, “We need more cups”, “Oh, there was a flood in the bathroom”, getting coffee, repairing coffee machines, etc., emails, administration. There is also all the work that is very transparent since basically everyone is responsible for the rooms or for generally keeping the building clean. So, you must constantly motivate people to really clean the kitchen from time to time. One thing is to clean one’s own dishes and the other is to clean the whole kitchen from time to time and you must encourage people to do that. Yes, being supportive in the background without pushing into the foreground.

To me it was clear that there was always some pressure coming from Jan. For example, there are times there are not as many people here. In such cases, it easily happens that you know everybody, and groups are formed that are relatively inaccessible for people who are new, and you often overlook that. For me, Jan has always taken care of breaking up these groups and said that this is not a place for private parties. It needs people who make sure that there is a certain atmosphere here and that is certainly the job of the association—to create opportunities again and again where you discuss what this atmosphere should look like, whether it provides what it is supposed to provide, and opportunities where you become aware of what the atmosphere does not make possible or what it excludes. So, self-reflection on a regular basis must be stimulated, I believe, so that the place remains alive in order to shake up structures that solidify again and again.

How is PAF linked to your own working life?

I spent a lot of time on the road with my work. So much so that it wasn’t worth keeping a room in Frankfurt. I gave up my room and then PAF really became a place where I could drop in on a weekly basis—a place to fall back upon. That was when I decided to invest here because it really made sense, even in my own life. Now I’m studying in Berlin and it doesn’t make sense to come here during the semester. I’m very busy with life and studying. So far, during the term breaks I have worked so much that I couldn’t come, and now it [PAF] has a different function in my life. But I fantasise … for example, I attend this Dance Week in August and notice that PAF suddenly becomes a place for me to try things out with others without too much logistical preparation. I don’t have to rent a studio and I don’t have to organise dancers, check their availability and think about how to pay them. I simply come to this dance week where I assume that others will show up who fancy dance as well and then we try something out here. So that’s what PAF means to me right now.

There’s no place in the world where I could say I’m going back to or I feel like I’m being taken care of or anything like it. And maybe PAF takes over this psychic function a little bit. Yes, and I’m impressed that someone creates a place where I can be as I want and I can find or seek support, at least without being obliged to anything … Jan doesn’t ask anything from me except that I pay 18 Euro per night. I don’t have to be part of a clique or anything. I don’t have to agree with everything else, I don’t have to become part of a commune and yet there is the feeling of being part of something or taking part in something.

It’s very cleverly done—that you think you are part of the whole thing. And I still don’t know to what extent I’m part of it. You also have to process this feeling of being part of it. You return and it’s not as you thought it would be. There are other people there [at PAF] or—whatever. And you’re different yourself and it feels completely different now. The feeling changes over time. Nobody here is responsible for making me feel good when I get here. Sometimes I arrive and there are friends, and sometimes I arrive and the friends are totally busy. Sometimes I arrive and the building is empty, and then I walk up the street with my suitcase and have to look for a room. But, of course, PAF is not self-organised. To call it self-organised is a means to an end. As you said, there are also certain decisions made, at least I was told, not to renovate the whole place in a way that makes it look like a hotel, so that no one gets the idea it might be one. When certain things don’t work, or don’t work well enough you understand: “Ah okay, there’s nobody here to take care of it.” It’s really strategic, but that’s what makes things happen. You feel like you are part of it, and in fact you can change things and be proactive, and then you are part of it. It provides for an attitude, I think. The purpose, in my opinion, is to create a certain attitude towards the environment and towards others. I think that’s very strong and I notice that it is spreading.

What is important within PAF? What keeps this place alive?

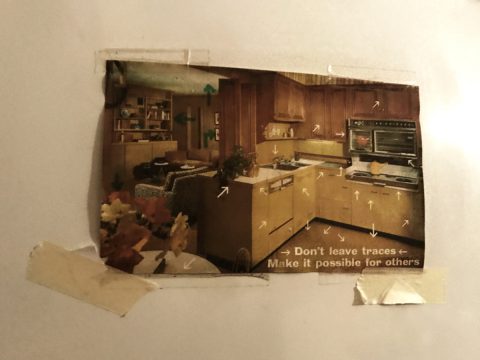

There are the three known rules: The doer decides. I’ll just name them now in their simplicity and incompleteness. The doer decides. Make it possible for others. Don’t leave traces. Those are, I think, the main rules. And then there are certain rules towards the village. You shouldn’t do experimental performances outside the PAF area. And not making noise too late at night, outside the designated spaces.

We now want to introduce a fourth rule, or we are right now discussing whether it is necessary. It would be called: Assume asymmetry.

The doer decides means that there is no responsible person who has to approve your decision first. Of course, it has limits and you can see that in the next rule. Make it possible for others. With “it”, I always ask myself what that means. Make it possible. That’s the biggest question mark for me. But, of course, the Doer shouldn’t do anything that makes certain things impossible for others. For example, the small everyday things, like to occupy a studio space over weeks. And then the third rule, Don’t leave traces, is central because nobody is responsible for tidying up. In such buildings—it regularly happens here—everyone in the whole building has to take the cups out of the rooms. All things move naturally. The furniture, everything, moves back and forth through the rooms. And then at some point there are no more cushions and you don’t know where all the cushions have gone. The yoga mats have disappeared. There really was a big pile of yoga mats once. We don’t know where they are. They are wandering around somewhere. For sure, nobody stole the yoga mats, but they disappeared somewhere. Under some bed or whatever. And that’s of course difficult when there’s no staff to check what’s under the beds of 50 rooms. Don’t leave traces is one of the most important rules for me even though I understand that—we discuss it—it is also important to leave traces. Sometimes things are not as they are supposed to be, and then it is important to thematise them in a way that is now not only intelligible for the people who are there immediately, but that these things can also carry on into the larger group. So that it becomes a common concern and that something about it can change. In this respect, the Don’t leave traces can also become a problem. Sometimes it also becomes a problem when people say, “No I want to say something now, and I want to make a poster about it which is hanging on the wall”, and then you are already negotiating. Assume asymmetry has to do with that. Here the principle applies—and I think this refers very strongly to Rancière and the ideas of Rancière—that all are equal in the encounter. That no one should teach anyone else here, but that we learn together, from each other and with each other. And we learn by dealing with a certain cause and with what’s happening here. And yet you have to realise that some people take up more space than others and some are more cautious and that problems can arise over this. Or that there are different sensitivities in general. Some are afraid to come here—and you shouldn’t try to help everyone. But I do think that you can understand how people who arrive here feel. If you have the impression that someone is suffering too much, you can approach them without being patronising. Or, we have talked a lot about gender dynamics now due to #metoo and all of that should also be covered by the rule Assume asymmetry. It means that not only is everyone responsible for themselves but also for a social cohesion. And for that you need some empathic abilities and an appeal for self-reflection. To question oneself again and again: what generates my behaviour in a group?

Would you change something in this place?

I think I would like to get involved with dance here in the near and medium run. I don’t know if I would change something. But I want to get involved with things—or work more artistically here myself. So far it has been a place where I mainly did intellectual work, but now that I want to dance more it is at least my intention to propose to do more things here. I have the impression that fewer pieces have been produced here lately. It became increasingly a place of exchange, where practices are exchanged, where there is a lot of work in the field of philosophy, very exciting work, but where I see fewer and fewer showings. Where fewer and fewer people make art. In the beginning, I think this was what the first 40 people mainly did here. There was an intensive examination of artistic questions. And that’s lagging behind a bit at the moment. I would like to relaunch that.

What is it that PAF, the place, cannot afford to lose?

For me, that would be the tension between seriousness on the one hand and pleasure or joy on the other, or the playfulness with a focus on work. The place mustn’t lose that. And then the openness and the ability to redefine itself again and again without losing these things.

What do you hope for the future for PAF as a place of work and for your own involvement with this place?

I want people to stay tuned and PAF to continue to benefit. And that you can negotiate again and again what this place is for … that you don’t negotiate so much what this place stands for but that you clarify again and again what is happening here and what is happening in this place. And that it stays alive. Maybe that’s what I wish for PAF.

Before ownership of the PAF building has been collectivised amongst 50 people, Jan had found and bought the building in 2005.

“I would not mind that more of us internalize the new-socio-anarchistic mindset that is behind the principles of PAF to dissolve principles of efficiency, to dissolve causality [and instead] celebrate inconsequentiality, contradiction and complexity.

(Jan Ritsema)

Things are not simple, and they do not need to be simplified, because things are complex and always on the move.”

Valentine joined Jan Ritsema at a very early stage and co-organises PAF

Berno has been part of the PAF universe since the very beginning…